Understanding the Role of Religion in America’s Founding

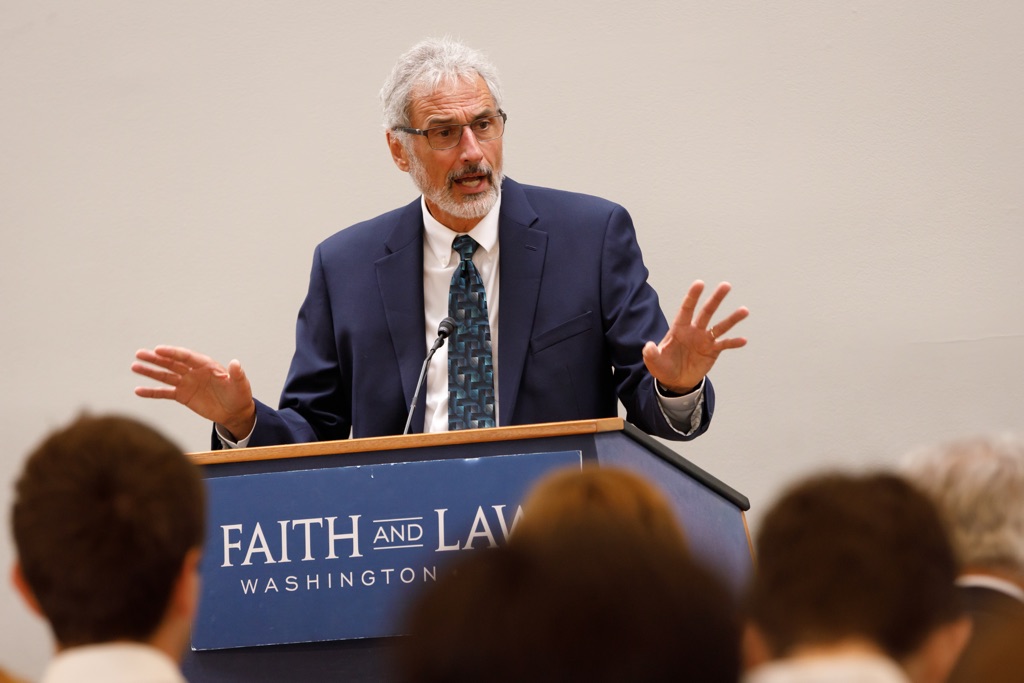

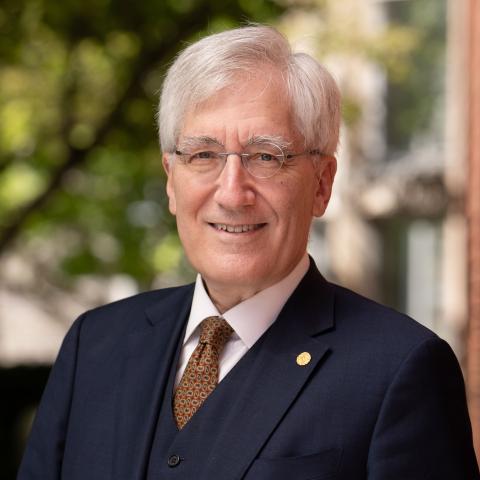

Did America have a Christian founding? That is the question we asked Dr. Mark David Hall to discuss at Faith and Law’s annual leadership conference on October 4. Author of numerous books on religion’s role in American history, Hall teaches at Regent University’s Robertson School of Government and is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Religion, Culture & Democracy.

Hall began by taking issue with the two dominant narratives about religion’s role at the Founding. The first – promoted by some popular Christian authors and often associated with the idea of Christian nationalism – is that the Founders intentionally sought to create a godly Christian nation. The second – espoused by many legal scholars and professors – is that the Founders were all Deists who “consciously attempted to create a godless constitution and tried to strictly separate church and state.”

Both views are plagued with historical inaccuracies, said Hall. In addition to Lockean liberalism, the Scottish school of moral sense, and the common law tradition, “the Founders were influenced in important ways by Christian ideas or ideas developed within the Christian tradition of political reflection.”

In a fascinating tour of key documents of early American history, Hall cited biblical references in the Puritan compact and the colonial charters in Calvinist Massachusetts, Anglican Virginia – and even in Quaker Pennsylvania. Calvinists lent theological support for the War for Independence, which British Loyalists “clearly associated with the Presbyterian faith.” Most importantly, the “central sentence” of the Declaration of Independence – that all men are that all men are created equal, that they are endowed, by their Creator, with certain unalienable rights – “rests on a theological proposition,” the Imago Dei.

Things get more interesting with the Constitution because of its omission of the Almighty. But contra to the view that the Constitution is a “godless charter,” Hall argued that the nation’s governing architecture belies a thoroughly Christian understanding of human nature. Madison’s shrewd insight in Federalist 51 that men are not angels explains why the American constitutional order is characterized by myriad checks on power, including federalism, separation of powers, and checks and balances between the branches.

A second tell-tale sign of Christian influence was the wide-spread belief in a natural moral law. “Everyone was convinced of this,” asserted Hall. “Every Supreme Court justice prior to John Marshall except for James Iredell is clearly on record saying Court could strike down any law of Congress that violated natural law. In the 18th century this was commonplace.” Liberty was not license.

A third example of Christian influence is the anti-establishment clause of the First Amendment. Rather than separate religion from public life, as many believe today, the amendment sought to protect churches from undue government influence.

What about Jefferson’s description of a wall of separation of church and state in his 1802 Letter to Danbury Baptists? According to Hall, the “wall” does not reflect the language of First Amendment (which Jefferson did not write), nor does it suggest that Jefferson sought to restrict Christians or churches from speaking out of faith on matters of public concern. Rather, as Jefferson himself penned, the wall reflects “the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience.” Jefferson’s own behavior also accords with this view. Two days after writing to the Danbury Baptists, Jefferson attended a church service held in the U.S. Capitol where he heard John Leland, himself an opponent of establishment, preach.

“Christianity had a very important impact on America’s founding,” Hall concluded. “It led to creation of the constitutional order, law and policies that have benefited all Americans.”

Faith and Law is a non-profit ministry started by policy makers and for policy makers.